4 Week 4: Complexity and Similarity

Slides

- 5 Complexity and Similarity (link)

4.1 Setup

As always, we first load the packages that we’ll be using:

library(tidyverse) # for wrangling data

library(tidylog) # to know what we are wrangling

library(tidytext) # for 'tidy' manipulation of text data

library(textdata) # text datasets

library(quanteda) # tokenization power house

library(quanteda.textstats)

library(quanteda.textplots)

library(wesanderson) # to prettify

library(stringdist) # measure string distance

library(reshape2)4.2 Replicating the Lecture

In this weeks lecture, we learned about similarity and complexity measures at the word- and document-level. We will follow the same order from the lecture slides.

4.3 Comparing Text

There are different ways to compare text, depending on the unit of analysis: - Character-level comparisons - Token-level comparison

4.3.1 Character-Level Comparisons:

Let’s start by using character-level comparison tools to evaluate two documents (in this case, two statements made by me on any given Ontario winter day):

doc_1 <- "By the professor’s standards, the weather in Ontario during the Winter term is miserable."

doc_2 <- "By the professor’s high standards, the weather in London during the Winter term is depressive."From ?stringdist, we know that “the longest common substring distance is defined as the number of unpaired characters. The distance is equivalent to the edit distance allowing only deletions and insertions, each with weight one.” We also learned about Levenshtein distance and Jaro distance. We can easily implement these using the stringdist function:

stringdist(doc_1,doc_2,method = "lcs")## [1] 27

stringdist(doc_1,doc_2,method = "lv")## [1] 20

stringdist(doc_1,doc_2,method = "jw")## [1] 0.1768849Each distance provides slightly different information about the relation between both documents. There are other distances that the stringdist function can compute. If this is something that interests you, there is more information about each measure in this paper.

Have I ever used these measure in my own work? Actually, yes. When combining a corpus of legislative speeches from the Ecuadorian Congress with a data set of Ecuadorian legislators, I matched the names of both data set using fuzzy matching or matching names that were closely related (even if they were not a perfect match). Here is an example of the code:

# Goal:

# - You have two data frames, `df_a` and `df_b`.

# - For each name in `df_a$CANDIDATO_to_MATCH`, you want to find the *closest* name in

# `df_b$CANDIDATO_MERGE` using Jaro–Winkler *distance* ("jw").

# - Because this is a distance, *lower is better* (0 means identical).

# - You treat it as a match when:

# (1) the *minimum* distance is below a threshold (0.4), AND

# (2) the best (minimum-distance) match is unique (i.e., no ties for the min).

for (i in 1:length(df_a$CANDIDATO_to_MATCH)) {

# Compute Jaro–Winkler distances from the current df_a name to *all* df_b candidate names

score_temp <- stringdist(

df_a$CANDIDATO_to_MATCH[i],

df_b$CANDIDATO_MERGE,

method = "jw"

)

# Identify the best match as the *minimum* distance

best_score <- min(score_temp, na.rm = TRUE)

best_idx <- which(score_temp == best_score)

# Accept the match only if:

# - the best (minimum) distance is below the threshold, AND

# - there is exactly one best match (no ties)

if (best_score < 0.4 & length(best_idx) == 1) {

# Assign the matched name from df_b into the merge column of df_a

df_a$CANDIDATO_MERGE[i] <- df_b$CANDIDATO_MERGE[best_idx]

} else {

# Otherwise, record NA (no confident/unique match)

df_a$CANDIDATO_MERGE[i] <- NA

}

}It saved me a lot of time. I still needed to validate all the matches and manually match the unmatched names.

4.3.2 Token-Level Comparisons:

To compare documents at the token level (i.e., how many tokens coincide and how often), we can think of each document as a row in a matrix and each word as a column. These are called document-feature matrices, or dfms. To do this using quanteda, we first need to tokenize our corpus:

doc_3 <- "The professor has strong evidence that the weather in London (Ontario) is miserable and depressive."

docs_toks <- tokens(rbind(doc_1,doc_2,doc_3),

remove_punct = T)

docs_toks <- tokens_remove(docs_toks,

stopwords(language = "en"))

docs_toks## Tokens consisting of 3 documents.

## text1 :

## [1] "professor’s" "standards" "weather"

## [4] "Ontario" "Winter" "term"

## [7] "miserable"

##

## text2 :

## [1] "professor’s" "high" "standards"

## [4] "weather" "London" "Winter"

## [7] "term" "depressive"

##

## text3 :

## [1] "professor" "strong" "evidence"

## [4] "weather" "London" "Ontario"

## [7] "miserable" "depressive"Now we are ready to create a dfm:

docs_dmf <- dfm(docs_toks)

docs_dmf## Document-feature matrix of: 3 documents, 13 features (41.03% sparse) and 0 docvars.

## features

## docs professor’s standards weather ontario

## text1 1 1 1 1

## text2 1 1 1 0

## text3 0 0 1 1

## features

## docs winter term miserable high london

## text1 1 1 1 0 0

## text2 1 1 0 1 1

## text3 0 0 1 0 1

## features

## docs depressive

## text1 0

## text2 1

## text3 1

## [ reached max_nfeat ... 3 more features ]Just a matrix (actually, a sparse matrix which becomes even sparser as the corpus grows). Now we can measure the similarity or distance between these two texts. The most straightforward approach is to correlate the occurrence of 1s and 0s across texts. One intuitive way to see what this means is to transpose the dfm and present it in a shape that you may find more familiar:

## docs

## features text1 text2 text3

## professor’s 1 1 0

## standards 1 1 0

## weather 1 1 1

## ontario 1 0 1

## winter 1 1 0

## term 1 1 0

## miserable 1 0 1

## high 0 1 0

## london 0 1 1

## depressive 0 1 1

## professor 0 0 1

## strong 0 0 1

## evidence 0 0 1Ok, now we just use a simple correlation test:

## text1 text2 text3

## text1 1.0000000 0.2195775 -0.4147575

## text2 0.2195775 1.0000000 -0.6250000

## text3 -0.4147575 -0.6250000 1.0000000From this, we can see that text1 is more highly correlated with text2 than with text3. Alternatively, we can use built-in functions in quanteda to obtain similar results without transforming our dfm:

textstat_simil(docs_dmf, margin = "documents", method = "correlation")## textstat_simil object; method = "correlation"

## text1 text2 text3

## text1 1.000 0.220 -0.415

## text2 0.220 1.000 -0.625

## text3 -0.415 -0.625 1.000We can use textstat_simil for a whole bunch of similarity/distance methods:

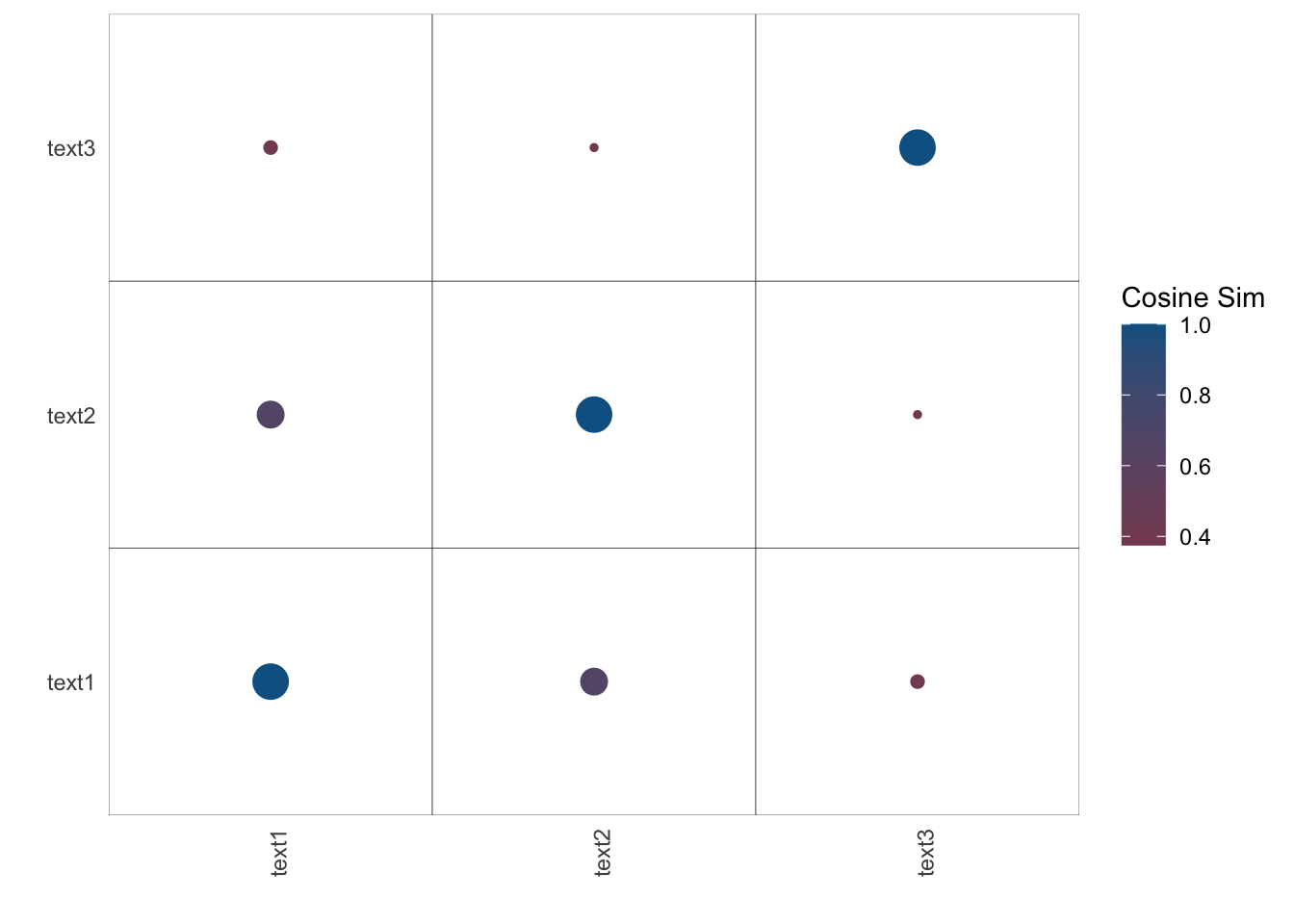

textstat_simil(docs_dmf, margin = "documents", method = "cosine")## textstat_simil object; method = "cosine"

## text1 text2 text3

## text1 1.000 0.668 0.401

## text2 0.668 1.000 0.375

## text3 0.401 0.375 1.000Cosine similarity is kind of an important method to know as we advance in the course. You can check out this app to get a visual example of cosine similarity, and this app to get a visual example of cosine similarity applied to text data.

textstat_simil(docs_dmf, margin = "documents", method = "jaccard")## textstat_simil object; method = "jaccard"

## text1 text2 text3

## text1 1.00 0.500 0.250

## text2 0.50 1.000 0.231

## text3 0.25 0.231 1.000

textstat_dist(docs_dmf, margin = "documents", method = "euclidean")## textstat_dist object; method = "euclidean"

## text1 text2 text3

## text1 0 2.24 3.00

## text2 2.24 0 3.16

## text3 3.00 3.16 0

textstat_dist(docs_dmf, margin = "documents", method = "manhattan")## textstat_dist object; method = "manhattan"

## text1 text2 text3

## text1 0 5 9

## text2 5 0 10

## text3 9 10 0We can also present these matrices as nice plots:

cos_sim_doc <- textstat_simil(docs_dmf, margin = "documents", method = "cosine")

cos_sim_doc <- as.matrix(cos_sim_doc)

# We do this to use ggplot

cos_sim_doc_df <- as.data.frame(cos_sim_doc)

cos_sim_doc_df %>%

rownames_to_column() %>%

# ggplot prefers

melt() %>%

ggplot(aes(x = as.character(variable),y = as.character(rowname), col = value)) +

geom_tile(col="black", fill="white") +

# coord_fixed() +

labs(x="",y="",col = "Cosine Sim", fill="") +

theme_minimal() +

theme(axis.text.x = element_text(

angle = 90,

vjust = 1,

hjust = 1)) +

geom_point(aes(size = value)) +

scale_size(guide = 'none') +

scale_color_gradient2(mid="#A63446",low= "#A63446",high="#0C6291") +

scale_x_discrete(expand=c(0,0)) +

scale_y_discrete(expand=c(0,0))## Using rowname as id variables## Ignoring unknown labels:

## • fill : ""

Noise!

4.4 Complexity

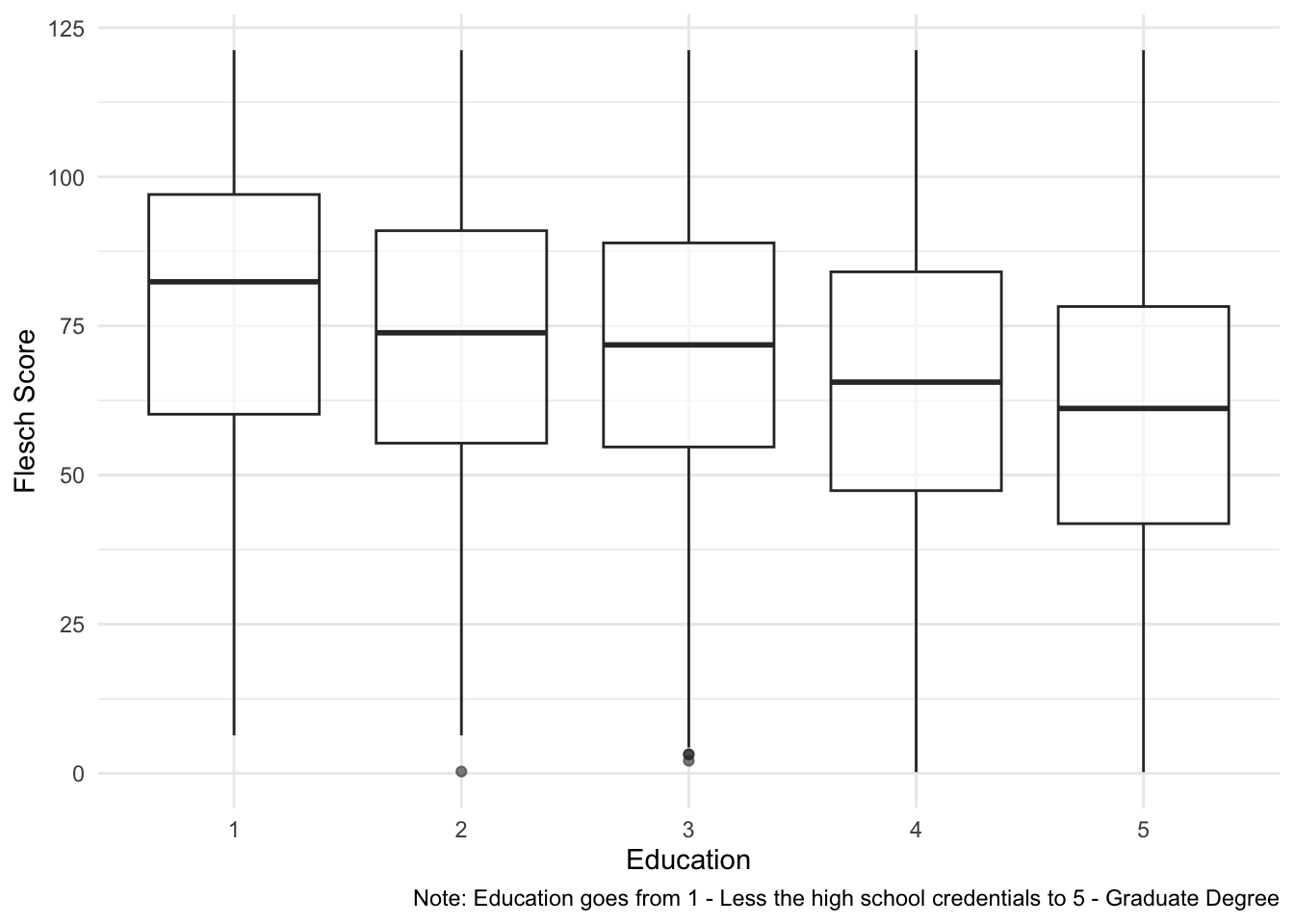

From this week’s lecture (and one of the readings), we know that another way of analyzing text is by computing its complexity. In Schoonvelde et al. (2019), “Liberals Lecture, Conservatives Communicate: Analyzing Complexity and Ideology in 381,609 Political Speeches,” the authors use Flesch’s Reading Ease Score as a measure of “complexity,” or readability (see ??textstat_readability for the formula and other readability measures). Flesch’s Reading Ease Score ranges from 0 to 100, where higher values indicate less complex (more readable) text. For example, a score between 90 and 100 suggests a text that can be understood by a 5th grader; a score between 0 and 30 suggests a text that is typically understandable for college graduates and professionals. The score is computed using the average sentence length, the number of words, and the number of syllables.

Let’s apply the readability score to some open-ended questions from the 2020 ANES survey, and see how these correlate to the characteristics of the respondents.

## # A tibble: 6 × 9

## V200001 like_dem_pres dislike_dem_pres

## <dbl> <chr> <chr>

## 1 200015 <NA> nothing about s…

## 2 200022 <NA> He wants to tak…

## 3 200039 He is not Donald Tru… <NA>

## 4 200046 he look honest and h… <NA>

## 5 200053 <NA> Open borders, l…

## 6 200060 he is NOT Donald Tru… <NA>

## # ℹ 6 more variables: like_rep_pres <chr>,

## # dislike_rep_pres <chr>, income <int>,

## # pid <int>, edu <int>, age <int>We have open-ended survey questions that ask respondents what they like and dislike about the Democratic (Joe Biden) and Republican (Donald Trump) 2020 U.S. presidential candidates before the election. Note that survey respondents could opt out of the question and were assigned an NA.

Let’s check:

read_like_dem_pres <- textstat_readability(open_srvy$like_dem_pres,measure = "Flesch")## Warning: NA is replaced by empty string## # A tibble: 15 × 2

## like_dem_pres read_like_dem_pres

## <chr> <dbl>

## 1 <NA> NA

## 2 <NA> NA

## 3 He is not Donald Trump. 100.

## 4 he look honest and his po… 54.7

## 5 <NA> NA

## 6 he is NOT Donald Trump !!… 100.

## 7 he has been in gov for al… 89.6

## 8 <NA> NA

## 9 he is wanting to do thing… 96.0

## 10 <NA> NA

## 11 Candidato adecuado para l… -10.8

## 12 <NA> NA

## 13 <NA> NA

## 14 Everything he stands for. 75.9

## 15 He is very intuned with h… 81.9Makes sense: the third row is quite easy to ready, the fourth row is a bit more complex, and the eleventh row is impossible to read because it is in Spanish.

open_srvy %>%

# Remove people who did not answer

filter(edu>0) %>%

# Remove negative scores

filter(read_like_dem_pres>0) %>%

ggplot(aes(x=as.factor(edu),y=read_like_dem_pres)) +

geom_boxplot(alpha=0.6) +

# scale_color_manual(values = wes_palette("BottleRocket2")) +

# scale_fill_manual(values = wes_palette("BottleRocket2")) +

theme_minimal() +

theme(legend.position="bottom") +

labs(x="Education", y = "Flesch Score",

caption = "Note: Education goes from 1 - Less the high school credentials to 5 - Graduate Degree")## filter: removed 131 rows (2%), 8,149 rows remaining

## filter: removed 4,412 rows (54%), 3,737 rows remaining

Look at that… having a degree makes you speak more complicated.

4.5 Exercise (Optional)

- Extend the analysis of the ANES data using other readiability scores and/or other variables. Alternatively, use other surveys with open-ended questions (e.g., CES).

- If you wanted to use a similarity/distance measure to explore the ANES/CES open-ended responses, how would you go about it? What would you be able to compare using only the data provided?