3 Lecture 2: Introduction to Causal Inference

Slides

- 3 Introduction to Causal Inference (link)

3.1 Introduction

We now dive deeper into causal inference and the counterfactual problem. We show why randomized trials solve the counterfactual problem, but also why it remains a challenge when using observational data.

The lecture slides are displayed in full below:

Figure 3.1: Slides for 3 Introduction to Causal Inference.

3.2 Vignette 2.1

Usually, we do not know the data-generating process, but here, we are gods. Let’s create a world where taking treatment A (e.g., taking a pill) positively affects Y (e.g., health) by one unit. Let’s run an experiment.

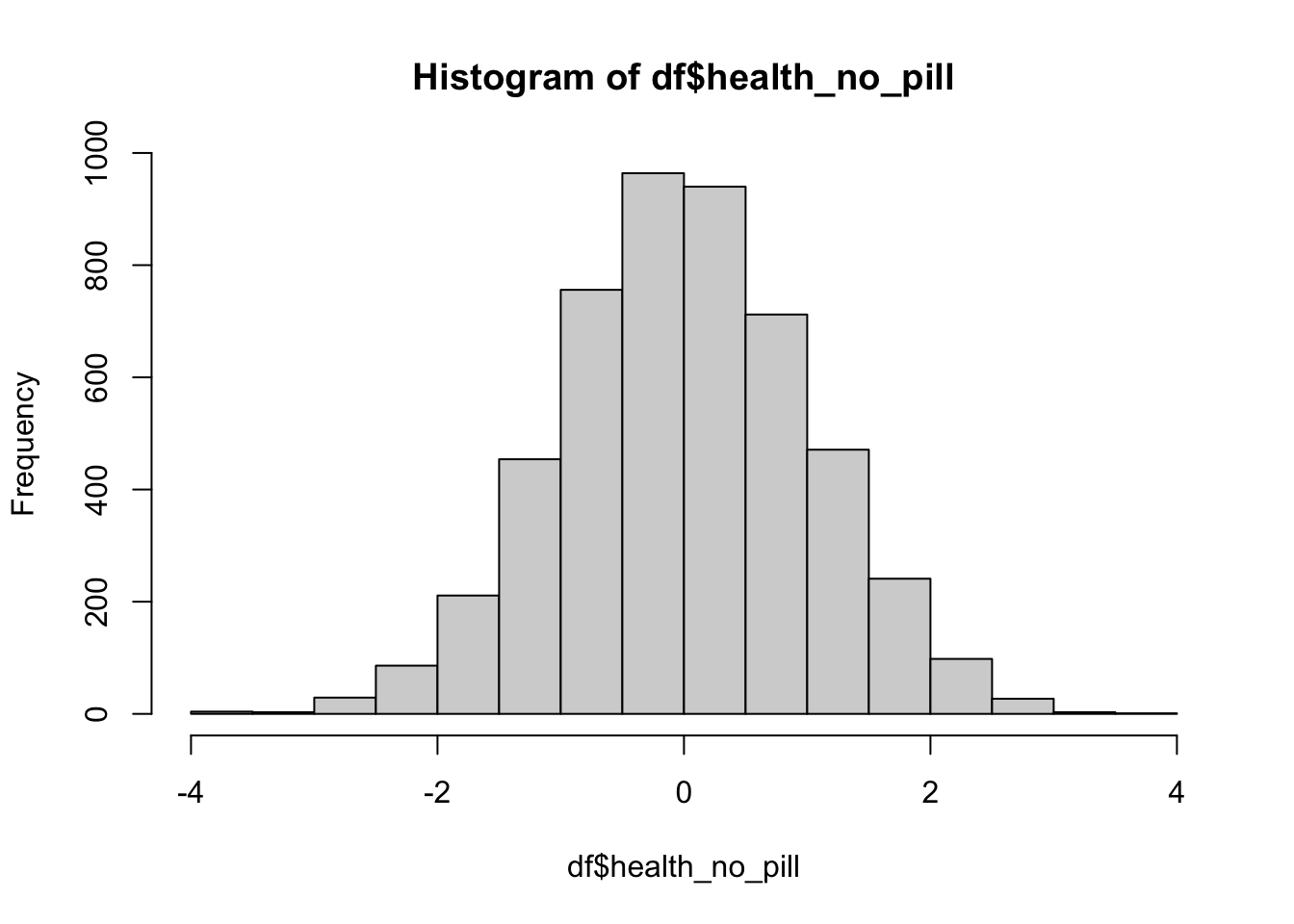

df <- data.frame(

# Simulate baseline health outcomes *without* treatment for 5,000 individuals

health_no_pill = rnorm(5000),

# Randomly assign treatment: pill = 1 (treated) or 0 (control)

pill = sample(c(0, 1), 5000, replace = TRUE)

)

# Visualize the distribution of baseline (no-pill) health outcomes

hist(df$health_no_pill)

| Var1 | Freq |

|---|---|

| 0 | 2553 |

| 1 | 2447 |

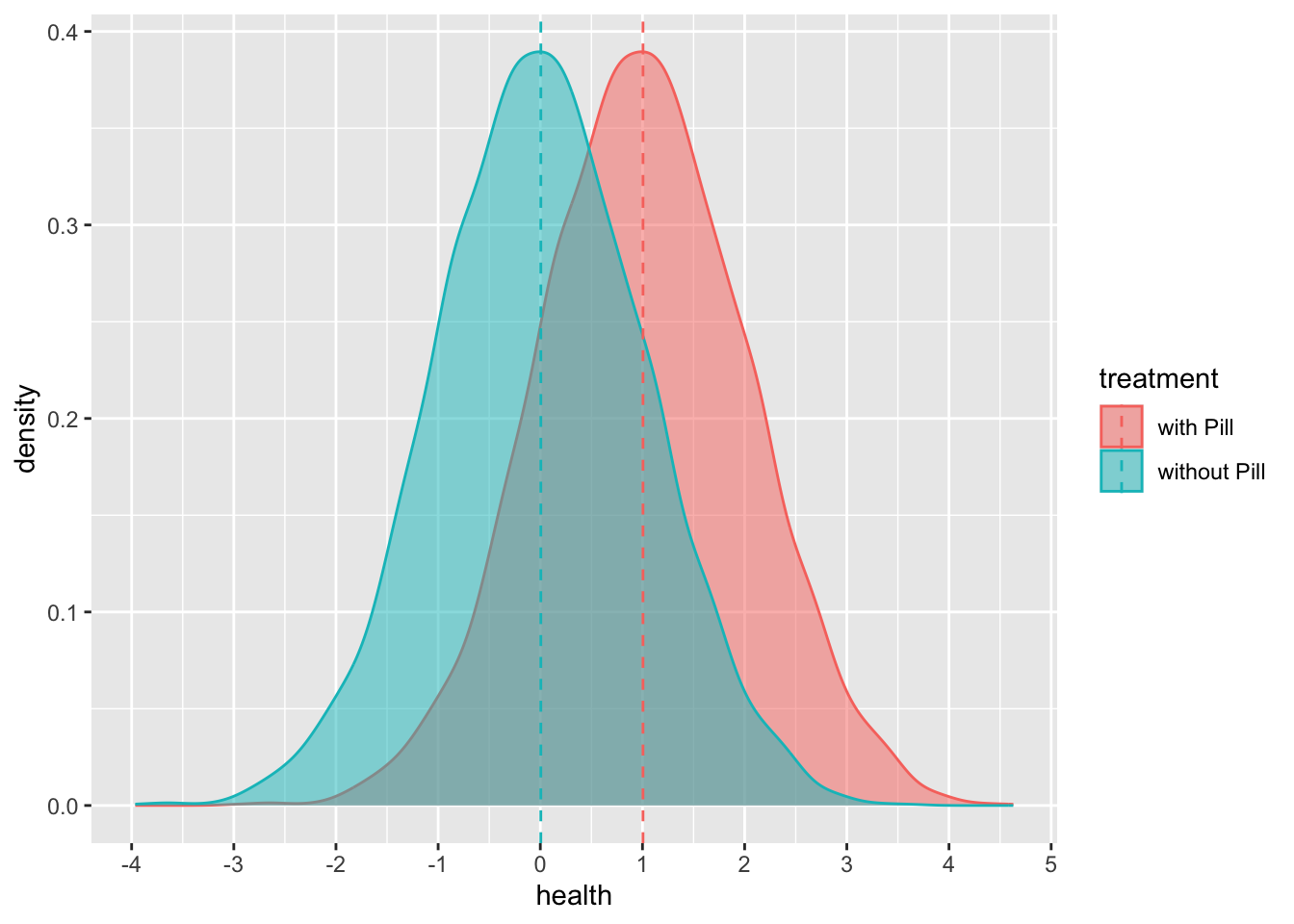

Now we can create our counterfactual:

df <- df %>%

# Define the potential outcome under treatment (A = 1):

# health_w_pill = health_no_pill + 1 implies a constant treatment effect of +1 for everyone.

mutate(health_w_pill = health_no_pill + 1) # Y(1): the potential outcome if treatedLet’s look at our counterfactual:

# Reshape the two potential outcomes into a long format for easy plotting/comparison

health_w_pill <- cbind.data.frame(df$health_w_pill, "with Pill")

colnames(health_w_pill) <- c("health", "treatment")

health_no_pill <- cbind.data.frame(df$health_no_pill, "without Pill")

colnames(health_no_pill) <- c("health", "treatment")

# Stack the two datasets to compare distributions under treatment vs. no treatment

comparison_y <- rbind.data.frame(health_w_pill, health_no_pill)

comparison_y %>%

group_by(treatment) %>%

# Compute group means (used to add mean lines to the plot)

mutate(mean_health = mean(health)) %>%

ungroup() %>%

ggplot(aes(x = health, fill = treatment, color = treatment)) +

# Plot the distribution of health outcomes under each condition

geom_density(alpha = 0.5) +

scale_x_continuous(breaks = scales::pretty_breaks(n = 8)) +

# Add dashed vertical lines at the mean health for each condition

geom_vline(

aes(xintercept = mean_health, color = treatment),

linetype = "dashed"

)## ungroup: no grouping variables remain

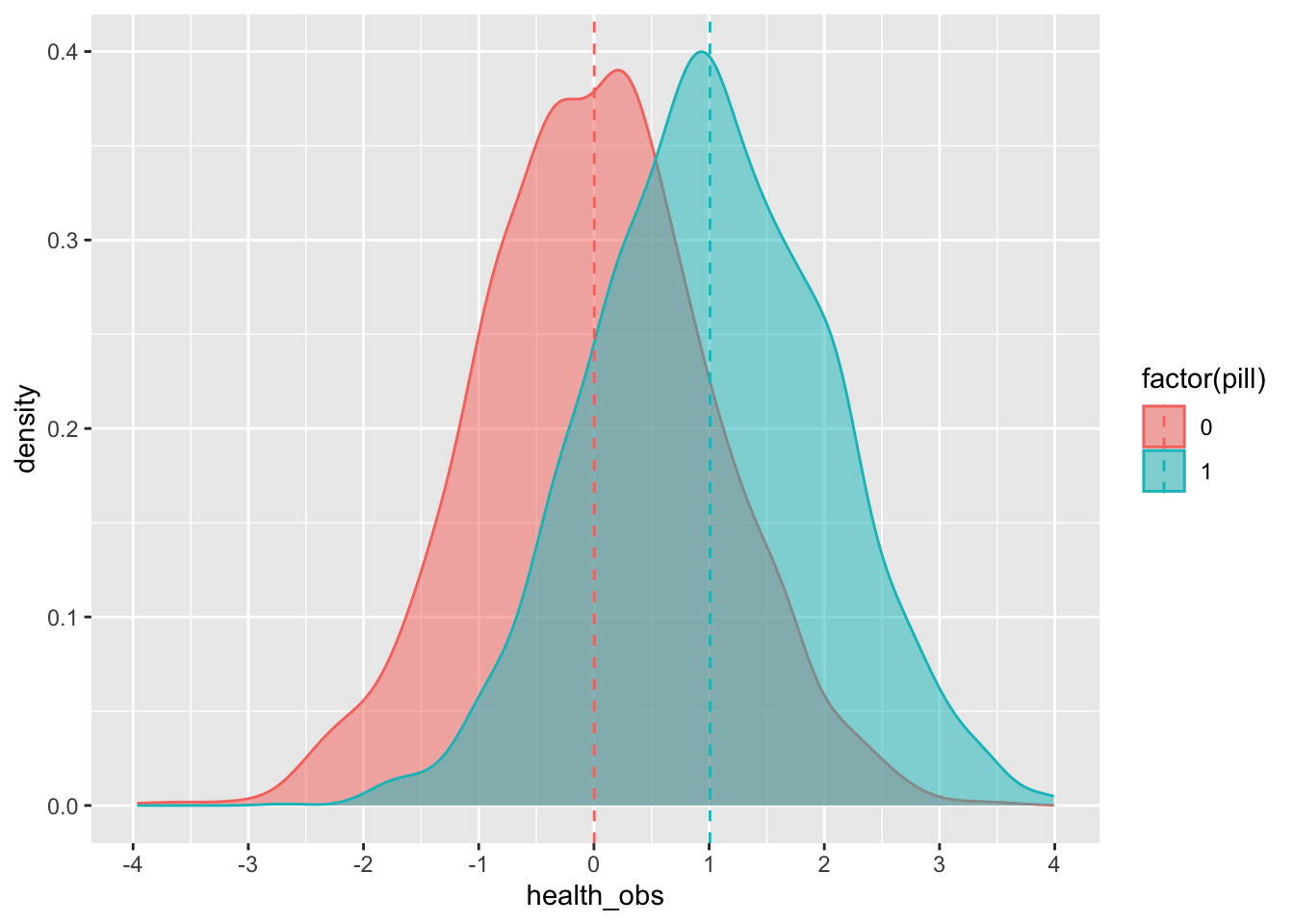

Now let’s give each individual the treatment (either the pill or a placebo):

df <- df %>%

# Construct the observed outcome:

# - if pill == 1, we observe the treated potential outcome Y(1)

# - if pill == 0, we observe the untreated potential outcome Y(0)

mutate(health_obs = ifelse(pill == 1, health_w_pill, health_no_pill))

# Inspect the first 10 rows to verify the observed outcome was assigned correctly

head(df, 10)## health_no_pill pill health_w_pill

## 1 0.73487435 1 1.7348744

## 2 -0.22740389 1 0.7725961

## 3 1.14278142 0 2.1427814

## 4 -0.78661487 1 0.2133851

## 5 1.14762293 0 2.1476229

## 6 -0.02646953 0 0.9735305

## 7 0.43260042 0 1.4326004

## 8 -0.22912635 1 0.7708737

## 9 -0.30914441 1 0.6908556

## 10 1.03198220 1 2.0319822

## health_obs

## 1 1.73487435

## 2 0.77259611

## 3 1.14278142

## 4 0.21338513

## 5 1.14762293

## 6 -0.02646953

## 7 0.43260042

## 8 0.77087365

## 9 0.69085559

## 10 2.03198220We can see the average effect of the pill on the treated group (remember from the lecture that the effect is, in essence, the difference between those who receive the treatment and those who do not):

df %>%

# Compare average observed health outcomes for treated (pill = 1) vs. control (pill = 0)

group_by(pill) %>%

summarize(health = mean(health_obs))## summarize: now 2 rows and 2 columns, ungrouped## # A tibble: 2 × 2

## pill health

## <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 0 0.0146

## 2 1 1.03Or we can plot it:

df %>%

group_by(pill) %>%

# Compute the mean observed health within treated vs. control groups

mutate(mean_health_obs = mean(health_obs)) %>%

ungroup() %>%

ggplot(aes(x = health_obs, fill = factor(pill), color = factor(pill))) +

# Plot the distribution of observed outcomes by treatment status

geom_density(alpha = 0.5) +

scale_x_continuous(breaks = scales::pretty_breaks(n = 8)) +

# Add dashed vertical lines at the group means

geom_vline(

aes(xintercept = mean_health_obs, color = factor(pill)),

linetype = "dashed"

)## ungroup: no grouping variables remain

3.3 Vignette 2.2

Ok… but what happens if we cannot randomize? What if we have observational data, such that…

df <- data.frame(income = runif(10000)) %>%

# Simulate baseline health without treatment (Y(0)).

# Here, health depends on a random component plus income (so income confounds health).

mutate(

health_no_pill = rnorm(10000) + income,

# Define the treated potential outcome (Y(1)) with a constant +1 treatment effect

health_w_pill = health_no_pill + 1

) %>%

# Assign treatment non-randomly: only higher-income individuals receive the pill

mutate(

pill = income > 0.7,

# Construct the observed outcome based on treatment assignment

health_obs = ifelse(pill == 1, health_w_pill, health_no_pill)

)

# Inspect the first 10 rows

head(df, 10)## income health_no_pill health_w_pill pill

## 1 0.2823133 -0.42813733 0.57186267 FALSE

## 2 0.3981014 0.93581402 1.93581402 FALSE

## 3 0.7386998 1.50385020 2.50385020 TRUE

## 4 0.5396686 0.05022473 1.05022473 FALSE

## 5 0.5054340 0.14850232 1.14850232 FALSE

## 6 0.3241123 -0.97063147 0.02936853 FALSE

## 7 0.9934859 1.45517296 2.45517296 TRUE

## 8 0.2820173 0.07810458 1.07810458 FALSE

## 9 0.7996215 2.11795395 3.11795395 TRUE

## 10 0.5867035 1.85616613 2.85616613 FALSE

## health_obs

## 1 -0.42813733

## 2 0.93581402

## 3 2.50385020

## 4 0.05022473

## 5 0.14850232

## 6 -0.97063147

## 7 2.45517296

## 8 0.07810458

## 9 3.11795395

## 10 1.85616613Let’s see what happens now to the estimated mean average ‘effect’ (remember from the lecture that the effect is, in essence, the difference between those who receive the treatment and those who do not):

## summarize: now 2 rows and 2 columns, ungrouped## # A tibble: 2 × 2

## pill health

## <lgl> <dbl>

## 1 FALSE 0.363

## 2 TRUE 1.88Oh no! That is more than the true effect of the pill, which we know is 1 because we created it. However, if we model this properly (this is an RDD!), then—remember from the lecture that the effect is, in essence, the difference between those who receive the treatment and those who do not:

df %>%

# Keep observations close to the cutoff (income = 0.7),

# mimicking the local comparison at the heart of a regression discontinuity design (RDD)

filter(abs(income - 0.7) < 0.01) %>%

# Compare mean observed outcomes just below vs. just above the cutoff

group_by(pill) %>%

summarize(health = mean(health_obs)) # BOOM!!## filter: removed 9,791 rows (98%), 209 rows remaining

## summarize: now 2 rows and 2 columns, ungrouped## # A tibble: 2 × 2

## pill health

## <lgl> <dbl>

## 1 FALSE 0.741

## 2 TRUE 1.773.4 Lecture Assignment

Using simulated data, describe (in text) and show (with plots) a plausible situation where a treatment has an effect, but the observed outcome is null. Tip: Before committing to an example, remember that a difference-in-differences approach requires two periods (change over time) and two groups (treatment and control).

Using a difference-in-differences approach, show how to estimate the true effect from your example.